Patterns of Orca-Human Aggression: Competing Hypotheses

More than 40 years ago, SeaWorld was capturing wild orcas for their entertainment parks. All but a couple were sent to their San Diego park for training as performers. For slightly over a year, from 1979 to 1981, the recent captives rotated among training, with some performing, and others spending time in the dolphin petting pool.

Visitors were able to interact with young, recently wild orcas with very little oversight by park staff. The orcas formed relationships with around two dozen repeat visitors. Co-authors of this writing, Anderson and Waayers, knew these orcas and have previously published a peer-reviewed paper based on the petting pool experience.

The orcas present during this time at the San Diego park were:

Winston (originally Ramu 3) a Southern Resident who was about 14 years old,

Kenau, Kandu 5, Canuck 2, and Katina who were all North Atlantic orcas of around 5 years of age, and Kasatka and Kotar who were North Atlantic orcas of around 2 years of age. (Shawn died soon after her arrival.)

Canuck 2, Katina, Kasatka, and Kotar were all known to have been in the petting pool. Kandu 5 and Canuck 2 were captured in the same year and both were sent to San Diego for training. Kandu 5 was a full-time performer during the main petting pool “era” but had likely been in the petting pool early on.

Consider the following observations:

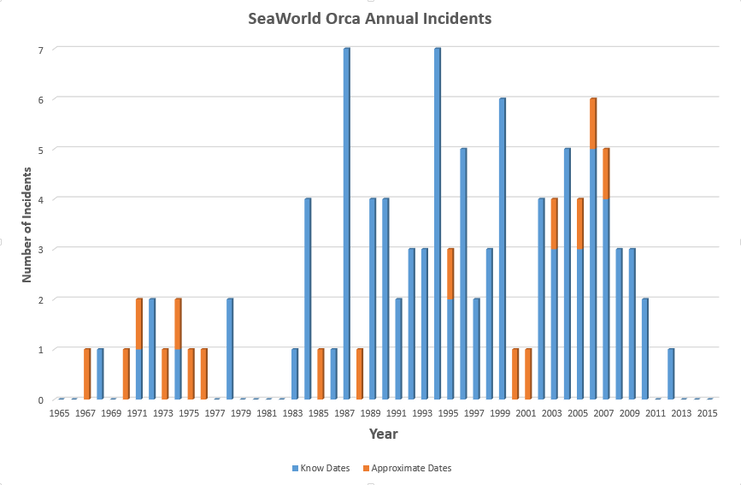

1) There have been aggressive incidents involving captive orcas essentially from the beginning, i.e. the mid 1960’s continuing at least until OSHA banned in-water work following the death of trainer Dawn Brancheau in 2010.

If you look at incidents by year, there is a curious gap or window in which no incidents occurred at SeaWorld. This gap starts during the petting pool era and continues for about 2 years, after which time the aggressions resumed.

Visitors were able to interact with young, recently wild orcas with very little oversight by park staff. The orcas formed relationships with around two dozen repeat visitors. Co-authors of this writing, Anderson and Waayers, knew these orcas and have previously published a peer-reviewed paper based on the petting pool experience.

The orcas present during this time at the San Diego park were:

Winston (originally Ramu 3) a Southern Resident who was about 14 years old,

Kenau, Kandu 5, Canuck 2, and Katina who were all North Atlantic orcas of around 5 years of age, and Kasatka and Kotar who were North Atlantic orcas of around 2 years of age. (Shawn died soon after her arrival.)

Canuck 2, Katina, Kasatka, and Kotar were all known to have been in the petting pool. Kandu 5 and Canuck 2 were captured in the same year and both were sent to San Diego for training. Kandu 5 was a full-time performer during the main petting pool “era” but had likely been in the petting pool early on.

Consider the following observations:

1) There have been aggressive incidents involving captive orcas essentially from the beginning, i.e. the mid 1960’s continuing at least until OSHA banned in-water work following the death of trainer Dawn Brancheau in 2010.

If you look at incidents by year, there is a curious gap or window in which no incidents occurred at SeaWorld. This gap starts during the petting pool era and continues for about 2 years, after which time the aggressions resumed.

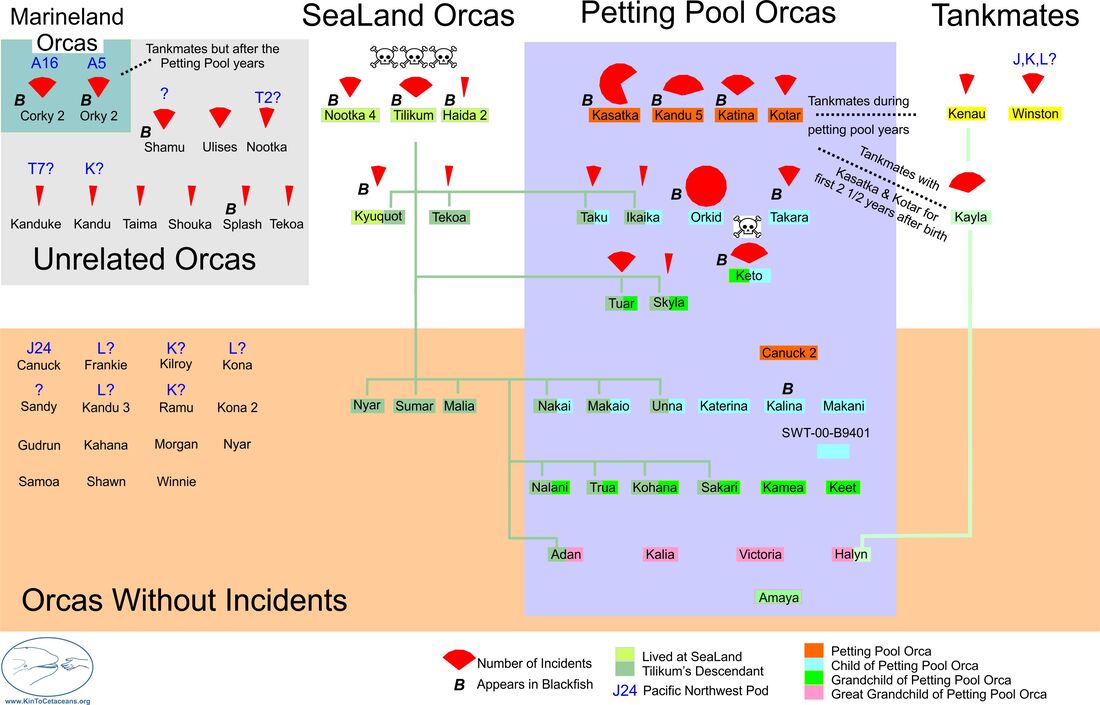

2) By a significant margin, the orcas perpetrating the aggressions are the petting pool orcas, their tank mates during the petting pool era, and the descendants of both groups.

3) In their peer-reviewed paper, Anderson and Waayers noted: "Even though the petting pool orcas were between two and five years of age, their mental maturity appeared roughly equivalent to a human at the age of mid-to-late teens." [1]

Note particularly Kotar and Kasatka. They were just 2 years old at the beginning of the petting pool era and had been living wild just one year prior. They never harmed a visitor during this period, and while they enjoyed fun interactions, they also exhibited quite mature and intelligent behavior. From the perspective of the human, imagine interacting with another human two-year-old who outweighed you by 13 times. It would likely be fraught with peril. But the humans who interacted with those young orcas ranging from 2-5 years of age were not harmed by their massive cetacean playmates during this period. Of course, a significant fact here is that orcas are born precocious after an 18-month gestation, and yet have essentially the same lifespan as humans. So being under 6 years of age has very different implications across the two species.

4) Although in all likelihood, many tens of thousands of visitors stopped by the petting pool during that era, the orcas formed relationships with only about 2 dozen, who were repeat visitors. Typically, these “orca friends” were individuals who were willing to become soaked in cold salt water, were not intimidated by a large mouth filled with sharply pointed teeth, or by placing their hands inside those mouths to give tongue and gum rubs to the orcas. And they were humans who enjoyed the idea of seeking contact with “alien” species, and wished to connect to the orcas as fellow intelligent beings, without practical agendas in mind.

Note particularly Kotar and Kasatka. They were just 2 years old at the beginning of the petting pool era and had been living wild just one year prior. They never harmed a visitor during this period, and while they enjoyed fun interactions, they also exhibited quite mature and intelligent behavior. From the perspective of the human, imagine interacting with another human two-year-old who outweighed you by 13 times. It would likely be fraught with peril. But the humans who interacted with those young orcas ranging from 2-5 years of age were not harmed by their massive cetacean playmates during this period. Of course, a significant fact here is that orcas are born precocious after an 18-month gestation, and yet have essentially the same lifespan as humans. So being under 6 years of age has very different implications across the two species.

4) Although in all likelihood, many tens of thousands of visitors stopped by the petting pool during that era, the orcas formed relationships with only about 2 dozen, who were repeat visitors. Typically, these “orca friends” were individuals who were willing to become soaked in cold salt water, were not intimidated by a large mouth filled with sharply pointed teeth, or by placing their hands inside those mouths to give tongue and gum rubs to the orcas. And they were humans who enjoyed the idea of seeking contact with “alien” species, and wished to connect to the orcas as fellow intelligent beings, without practical agendas in mind.

Consider the following two hypotheses that might explain the preceding observations of peaceful interaction between relatively frail humans and orcas which could conceivably do great harm to them, followed by aggressions by those same orcas and their associates and offspring.

Waayers: The petting pool orcas were young and new to captivity, and so had not yet suffered the mental health degradations that ravage intelligent animals that have been long confined. And they enjoyed unstructured interaction and play with humans. They did what they liked for the most part, and had essentially no demands placed on them, and few conditions for getting their food or other rewards. Then they were placed in the strictly controlled environment associated with training, where affection was used primarily as a reward for doing the right thing (although trainers did, of course, sometimes engage in "free play" with them). In addition, these orcas were thrust into the company of new whale companions, including Winston, who likely was badly damaged in terms of his mental health by his experiences with humans and his long captivity. Winston may or may not have communicated with the young orcas, but just being around him may have changed their attitudes towards humans.

A freedom-loving human in a similar situation (able to interact with fellow intelligent beings in an unstructured and loving environment, and then later placed in controlled confinement where most actions are judged and freedoms greatly restricted) might show a similar transformation towards more antisocial behavior.

In addition, the tedium and restrictions of captivity almost certainly took a toll on the mental health of all the captive orcas, and the relatively happy-go-lucky youngsters succumbed to the mental derangement that so many intelligent captive animals, from cuttlefish to elephants, experience.

It should also be considered that the higher frequency of petting pool orca aggression could also be an artifact of the small sample size involved and/or the normal variance of behaviors among individuals.

Waayers: The petting pool orcas were young and new to captivity, and so had not yet suffered the mental health degradations that ravage intelligent animals that have been long confined. And they enjoyed unstructured interaction and play with humans. They did what they liked for the most part, and had essentially no demands placed on them, and few conditions for getting their food or other rewards. Then they were placed in the strictly controlled environment associated with training, where affection was used primarily as a reward for doing the right thing (although trainers did, of course, sometimes engage in "free play" with them). In addition, these orcas were thrust into the company of new whale companions, including Winston, who likely was badly damaged in terms of his mental health by his experiences with humans and his long captivity. Winston may or may not have communicated with the young orcas, but just being around him may have changed their attitudes towards humans.

A freedom-loving human in a similar situation (able to interact with fellow intelligent beings in an unstructured and loving environment, and then later placed in controlled confinement where most actions are judged and freedoms greatly restricted) might show a similar transformation towards more antisocial behavior.

In addition, the tedium and restrictions of captivity almost certainly took a toll on the mental health of all the captive orcas, and the relatively happy-go-lucky youngsters succumbed to the mental derangement that so many intelligent captive animals, from cuttlefish to elephants, experience.

It should also be considered that the higher frequency of petting pool orca aggression could also be an artifact of the small sample size involved and/or the normal variance of behaviors among individuals.

Anderson: Winston was the senior orca present in a “patchwork” pod of captives. It would be natural for him to assume leadership. The petting pool orcas would have shared with their new pod mates their experiences with the “orca-friend” class of humans who behaved so differently from the “trainer” class of humans. But could orcas from different geographic regions communicate with each other? Howard Garrett in a Jan 2022 email:

“In 1967 a Southern Resident orca (Skana, captured in Puget Sound) was kept at Vancouver Aquarium. In April, 1968 Skana was joined by Hyak II, a Northern Resident. Hyak II learned So. Resident calls from Skana, who died in 1980. Later in 1980 two Icelandic orcas, Finna and Bjossa, were put in the same pool with Hyak II, who soon learned and used Icelandic calls. Presumably he also learned what they mean. So Hyak II became tri-lingual.”

The question is whether Winston, alone or in consultation, directed a more serious purpose into the petting pool orcas' play, having recognized an opportunity afforded by the absolutely unique circumstance of orcas and humans freely interacting with each other? Were the young orcas instructed to select for seemingly compatible humans and to treat them as pod mates? Is it beyond the pale to consider that highly intelligent, supremely social and cooperative non-humans might conceptualize a social/cooperative tactic to address their most pressing problem, captivity? Might an orca be forgiven for having an “orcamorphic” concept of how humans might react, i.e. humans would realize what orcas really are – intelligent “fellow travelers” undeserving of captivity?

To affect this, all aggressions were halted and remained so until it became apparent that this effort had failed. The orcas who had been directly involved (or informed of it by their parents) were the most frustrated at its failure. And thus the subsequent increased aggressions towards humans.

My personal experience was that Canuck introduced himself to me quite assertively. He surfaced from beneath the dolphin I had been interacting with and flicked it aside with his head. I had ignored the orcas on a couple prior visits. After this, whichever orca was in the pool would come right to me when I showed up. No further “introductions” were ever required. Was this an attempt at “recruitment” of an ally?

To affect this, all aggressions were halted and remained so until it became apparent that this effort had failed. The orcas who had been directly involved (or informed of it by their parents) were the most frustrated at its failure. And thus the subsequent increased aggressions towards humans.

My personal experience was that Canuck introduced himself to me quite assertively. He surfaced from beneath the dolphin I had been interacting with and flicked it aside with his head. I had ignored the orcas on a couple prior visits. After this, whichever orca was in the pool would come right to me when I showed up. No further “introductions” were ever required. Was this an attempt at “recruitment” of an ally?

We leave it to the reader to choose between these hypotheses or offer their own explanation.

[1] Note: From Howard Garrett, Co-Founder and president of the Board, Orca Network, (17 Jan 2022) responding to an email discussion we were having while writing this article:

[1] Note: From Howard Garrett, Co-Founder and president of the Board, Orca Network, (17 Jan 2022) responding to an email discussion we were having while writing this article:

“All this is a fascinating inquiry into comparative physical, behavioral and cognitive growth in humans and killer whales. I don’t have much to add other than observations of A73 and L98, both functionally competent at about age two (A73 a few months less, L98 a few months older). Also captive studies of vocalizing learned calls at about one year (sorry, I don’t have any citations handy), and Ridgway’s paper on orca neural development.

I’d like to see more scientific attention to this. It’s important to show that Tokitae, captured at about age four, has far more recall of her life before capture than a human would have.”