Howard Garrett

Orca Network

[email protected]

www.orcanetwork.org

Do orcas use symbols?

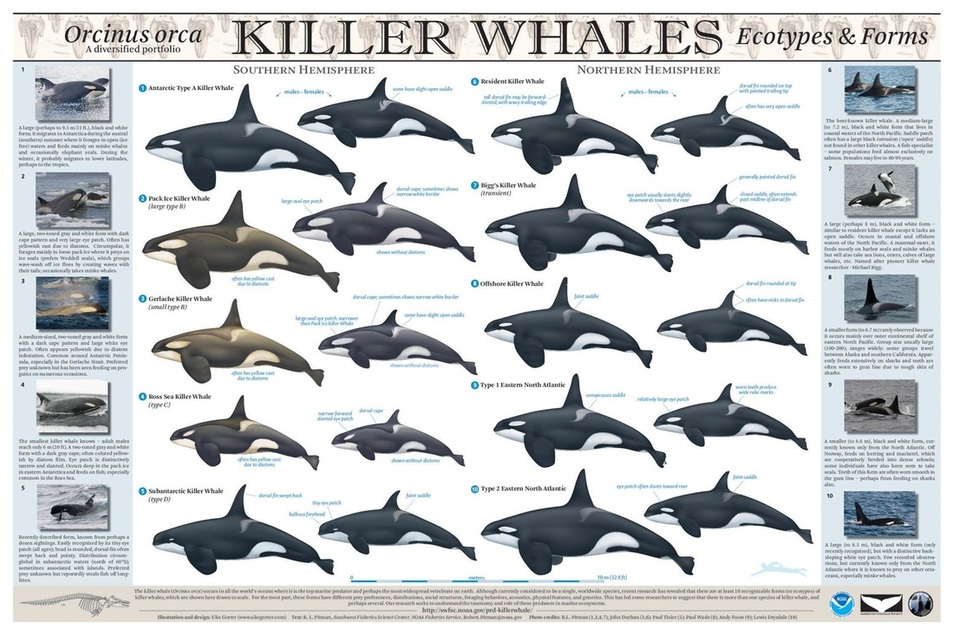

Two distinct cultural communities of orcas inhabit the inland marine waters between Washington State and British Columbia. These two groups, among dozens of orca communities worldwide, are known as the Southern residents and transients.

The two communities do not interbreed and are genetically separated by many thousands of years, possibly hundreds of thousands, and each uses a completely distinct set of vocalizations. Their diets are mutually exclusive – residents eat fish, while transients eat mammals.

Orca Network

[email protected]

www.orcanetwork.org

Do orcas use symbols?

Two distinct cultural communities of orcas inhabit the inland marine waters between Washington State and British Columbia. These two groups, among dozens of orca communities worldwide, are known as the Southern residents and transients.

The two communities do not interbreed and are genetically separated by many thousands of years, possibly hundreds of thousands, and each uses a completely distinct set of vocalizations. Their diets are mutually exclusive – residents eat fish, while transients eat mammals.

Group size, habitat use and other behaviors are also very different from one another. Each community is a distinct cultural community, with its own social and mating systems and ceremonies. Family structures are not well understood for most communities, but northeast Pacific resident orcas remain together for life. There is no dispersal.

The two groups are on their way to becoming separate species (Hoelzel, et al. 1998). And yet, they are sympatric. There is no geographic separation. They cross paths in the same waters almost daily and are biologically capable of interbreeding, but don’t. This level of sympatric speciation by mammals is unprecedented.

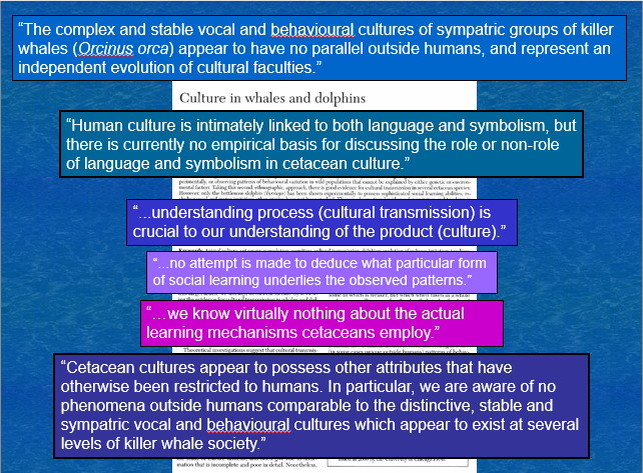

In 2001 a landmark paper was published in the British Journal of Behavioural and Brain Sciences called Culture in Whales and Dolphins, by Luke Rendell and Hal Whitehead (Rendell and Whitehead 2001). The authors reviewed every available field study of cetacean species, and experimental evidence from studies of captive dolphins, as well as field studies and developing theory about culture in other animals, mainly primates. In the abstract the authors conclude that:

|

“The complex and stable vocal and behavioural cultures of sympatric groups of killer whales (Orcinus

orca) appear to have no parallel outside humans (emphasis mine) and represent an independent evolution of cultural faculties.” |

The authors hoped to stimulate discussion and research on culture in orcas. They say:

|

“...understanding process (cultural transmission) is crucial to our understanding of the product (culture).”

|

Social learning is integral to their definition of culture and is referred to throughout the paper, but there is little description or inquiry about what form of social learning or transmission process may be involved. In fact:

|

“...no attempt is made to deduce what particular form of social learning underlies the observed patterns.” And…“we know virtually nothing about the actual learning mechanisms cetaceans employ.”

|

The authors go on to say . . .

|

“Human culture is intimately linked to both language and symbolism, but there is currently no empirical basis for discussing the role or non-role of language and symbolism in cetacean culture …”

|

And they say . . .

|

“Cetacean cultures appear to possess other attributes that have otherwise been restricted to humans. In particular, we are aware of no phenomena outside humans comparable to the distinctive, stable and sympatric vocal and behavioural cultures which appear to exist at several levels of killer whale society.”

|

An anomaly is something that is known to happen, but for which there isn’t any good explanation. For example, why do residents eat only fish, while transients eat only mammals? Or why do orca calls occur in three categories: “discrete,” “aberrant” and “variable” (Ford, 1991). Discrete calls are the approximately 7-17 typical calls by which a pod can be identified acoustically. They are often repeated every few seconds. Aberrant calls are based on discrete calls with some modification. Variable calls have so far defied classification, but are used most often during active socialization. These anomalies call out for a theory that can accommodate the observed behaviors.

Theory often precedes empirical studies. If there is currently no empirical basis for discussing the role or non-role of language and symbolism in cetacean culture, perhaps it is because there is little or no theoretical basis for doing so.

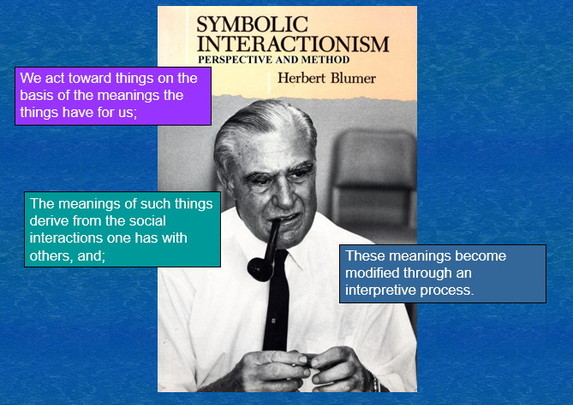

Many cetologists have observed that orcas live in complex and stable cultures without parallel except in humans. And yet the biological sciences have little or no background for discussing cultures at this level of complexity. Cetology can’t go much further in the discussion of orca cultures without drawing from other sciences that have long established backgrounds in describing the processes that underlie human cultures. That would be mainly sociology, specifically a sub-discipline of sociology called symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1969). But biology and sociology don’t usually consult with one another. They’re a little like residents and transients: they don’t speak the same language.

By combining the findings of Culture in Whales and Dolphins with symbolic interactionism (a venerable and very current theoretical model in sociology), the resulting synthesis may provide a sound basis for ascribing the use of symbols as the primary social learning process that facilitates the formation of the elaborate cultures found worldwide in orca societies.

Bottlenose dolphins have been taught artificial ‘languages,’ and can use abstract representations, or symbols, of objects, actions and concepts to guide their behavior (Herman 1994), AND stable, diverse and complex cultures have been found in killer whale societies. So any overall theory of orca behavior should consider the possibility that orcas communicate with some kind of language, i.e., that they use symbols to share group-specific meanings and thereby develop cultures. That would be symbolic interaction.

The best description of symbolic interactionism can be found in Symbolic Interactionism - Perspective and method (Blumer 1969), which is still required reading in most sociology and anthropology programs worldwide.

Symbolic interactionism has a long history in sociology. It began almost a hundred years ago with the German economist and sociologist, Max Weber (1864-1920) and the American philosopher, George Herbert Mead (1863-1931), both of whom emphasized subjective meaning as a major factor in human behavior and social process. Mead was inspired by Darwin, arguing that we should regard the human being in natural, evolutionary, terms. The individual and society are always in process through symbolic interaction, with patterns and meanings always emerging and changing or being reaffirmed over time.

The basic outline of symbolic interactionism is a set of three perspectives.

Theory often precedes empirical studies. If there is currently no empirical basis for discussing the role or non-role of language and symbolism in cetacean culture, perhaps it is because there is little or no theoretical basis for doing so.

Many cetologists have observed that orcas live in complex and stable cultures without parallel except in humans. And yet the biological sciences have little or no background for discussing cultures at this level of complexity. Cetology can’t go much further in the discussion of orca cultures without drawing from other sciences that have long established backgrounds in describing the processes that underlie human cultures. That would be mainly sociology, specifically a sub-discipline of sociology called symbolic interactionism (Blumer 1969). But biology and sociology don’t usually consult with one another. They’re a little like residents and transients: they don’t speak the same language.

By combining the findings of Culture in Whales and Dolphins with symbolic interactionism (a venerable and very current theoretical model in sociology), the resulting synthesis may provide a sound basis for ascribing the use of symbols as the primary social learning process that facilitates the formation of the elaborate cultures found worldwide in orca societies.

Bottlenose dolphins have been taught artificial ‘languages,’ and can use abstract representations, or symbols, of objects, actions and concepts to guide their behavior (Herman 1994), AND stable, diverse and complex cultures have been found in killer whale societies. So any overall theory of orca behavior should consider the possibility that orcas communicate with some kind of language, i.e., that they use symbols to share group-specific meanings and thereby develop cultures. That would be symbolic interaction.

The best description of symbolic interactionism can be found in Symbolic Interactionism - Perspective and method (Blumer 1969), which is still required reading in most sociology and anthropology programs worldwide.

Symbolic interactionism has a long history in sociology. It began almost a hundred years ago with the German economist and sociologist, Max Weber (1864-1920) and the American philosopher, George Herbert Mead (1863-1931), both of whom emphasized subjective meaning as a major factor in human behavior and social process. Mead was inspired by Darwin, arguing that we should regard the human being in natural, evolutionary, terms. The individual and society are always in process through symbolic interaction, with patterns and meanings always emerging and changing or being reaffirmed over time.

The basic outline of symbolic interactionism is a set of three perspectives.

- We act toward things on the basis of the meanings the things have for us

- The meanings of such things derive from the social interactions one has with others, and;

- These meanings become modified through an interpretive process.

Mead tried to understand concepts like self, mind and symbols as qualities developed by the human being as part of nature, part of our heritage in the animal kingdom.

Mead believed that humans are able to communicate symbolically with ourselves (that’s our inner voice) and with others, because

Self-awareness is an essential component of symbolic interaction. Selfhood means that the individual is able to see self in situations. Until recently, only humans and great apes had shown convincing evidence of mirror self-recognition. Tests in 2001 showed that bottlenose dolphins can use mirrors to investigate parts of their bodies that are marked (Reiss and Marino 2001). Thus, dolphins, already known to be able to use symbols, meet another essential requirement of symbolic interaction: self-awareness.

Observations of orca cultures indicate that orcas, the most highly encephalized dolphin, have combined self-recognition and the ability to use symbols, to construct cultural communities.

The capacity for taking the role of the other, or empathy, also known as Theory of Mind, is essential to the development of selfhood, symbol use, and culture. Role-taking is imagining the world from the perspective of another, and it is the perspectives of others that allow us to view ourselves. Taking the role of the other is necessary for learning our perspectives, for working through social situations, for knowing how to cooperate or organize or manipulate others, for loving, and for symbolic communication. We continually assess how others affect us, and how we affect them. Meaning is derived socially, as a process of mutual alignment, and is not simply an individual construction. Individuals seek self-interest through community affiliation, from which they derive meaning.

From this vantage point, orcas are seen as self-aware creative actors who take the role of others, interpret their circumstances and act according to what things mean to them, as developed in symbolic interactions with other members of their societies.

Over time, symbolic interaction creates and sustains culture. The culture of a society becomes the overall guide for the individual’s meanings, interpretations and actions. Mead used the term “generalized other” to describe the shared culture of the group. The “generalized other” is the generally understood set of perceptions, knowledge, values and rules. A generalized other develops in interaction and is used by individuals to control themselves. A generalized other is the guide for normal, civilized behavior; it is the system; it is the knowledge and conscience of the group that individuals are expected to follow. It’s ongoing – group behavior has to be continually modified to take account of all that happens. It’s adaptive (or maladaptive) which means interaction, as the basis of culture, plays a big role in the evolutionary process.

For example, for residents the generalized other says to eat only fish, while for transients, the generalized other says to eat only mammals. This on-going interaction with society is what maintains the appearance of stability.

The viewpoint expressed here is that orcas and humans have independently evolved (or converged) into symbol-using animals. Behavior based largely on symbolic interaction fosters the creation of complex cultures that allow action based on meaning, interpretation and choice, which can, and usually does, override genetic or environmental factors in determining behavior and speciation.

Self-recognition, role-taking, interpretation of the generalized other and use of symbols are all essential precursors for the development of culture, whether in orcas or humans.

The theory of symbolic interactionism may provide conceptual tools to help describe the form of social learning that underlies cultures in orca communities. By borrowing perspectives from symbolic interactionism to help understand recent findings of orca cultures, the resulting synthesis accounts for a wide variety of diverse data and ratchets the argument for cetacean culture (Garrett 2004). This synthesis opens a new window on the whales. As Rendell and Whitehead say:

Mead believed that humans are able to communicate symbolically with ourselves (that’s our inner voice) and with others, because

- we have highly developed brains,

- we rely heavily on society, and

- we are able to make many subtle and sophisticated sounds.

Self-awareness is an essential component of symbolic interaction. Selfhood means that the individual is able to see self in situations. Until recently, only humans and great apes had shown convincing evidence of mirror self-recognition. Tests in 2001 showed that bottlenose dolphins can use mirrors to investigate parts of their bodies that are marked (Reiss and Marino 2001). Thus, dolphins, already known to be able to use symbols, meet another essential requirement of symbolic interaction: self-awareness.

Observations of orca cultures indicate that orcas, the most highly encephalized dolphin, have combined self-recognition and the ability to use symbols, to construct cultural communities.

The capacity for taking the role of the other, or empathy, also known as Theory of Mind, is essential to the development of selfhood, symbol use, and culture. Role-taking is imagining the world from the perspective of another, and it is the perspectives of others that allow us to view ourselves. Taking the role of the other is necessary for learning our perspectives, for working through social situations, for knowing how to cooperate or organize or manipulate others, for loving, and for symbolic communication. We continually assess how others affect us, and how we affect them. Meaning is derived socially, as a process of mutual alignment, and is not simply an individual construction. Individuals seek self-interest through community affiliation, from which they derive meaning.

From this vantage point, orcas are seen as self-aware creative actors who take the role of others, interpret their circumstances and act according to what things mean to them, as developed in symbolic interactions with other members of their societies.

Over time, symbolic interaction creates and sustains culture. The culture of a society becomes the overall guide for the individual’s meanings, interpretations and actions. Mead used the term “generalized other” to describe the shared culture of the group. The “generalized other” is the generally understood set of perceptions, knowledge, values and rules. A generalized other develops in interaction and is used by individuals to control themselves. A generalized other is the guide for normal, civilized behavior; it is the system; it is the knowledge and conscience of the group that individuals are expected to follow. It’s ongoing – group behavior has to be continually modified to take account of all that happens. It’s adaptive (or maladaptive) which means interaction, as the basis of culture, plays a big role in the evolutionary process.

For example, for residents the generalized other says to eat only fish, while for transients, the generalized other says to eat only mammals. This on-going interaction with society is what maintains the appearance of stability.

The viewpoint expressed here is that orcas and humans have independently evolved (or converged) into symbol-using animals. Behavior based largely on symbolic interaction fosters the creation of complex cultures that allow action based on meaning, interpretation and choice, which can, and usually does, override genetic or environmental factors in determining behavior and speciation.

Self-recognition, role-taking, interpretation of the generalized other and use of symbols are all essential precursors for the development of culture, whether in orcas or humans.

The theory of symbolic interactionism may provide conceptual tools to help describe the form of social learning that underlies cultures in orca communities. By borrowing perspectives from symbolic interactionism to help understand recent findings of orca cultures, the resulting synthesis accounts for a wide variety of diverse data and ratchets the argument for cetacean culture (Garrett 2004). This synthesis opens a new window on the whales. As Rendell and Whitehead say:

|

“…there is a clear case for studying the cultural transmission of information directly as parts of the research agendas of the long-term field studies of whales and dolphins.”

|

Bibliography

Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism - Perspective and method. University of California Press.

Ford, John. K. B. 1991. Vocal traditions among resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in coastal waters of British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1454-1483.

Garrett, Howard. 2004, Do Orcas Use Symbols? http://www.orcanetwork.org/nathist/symbols.html

Herman, Louis. M., Pack, A. A. and Wood, A. M. 1994. Bottlenose dolphins can generalize rules and develop abstract concepts. Marine Mammal Science 10:70-80.

Hoelzel, A. R., Dahlheim, M. & Stern, S. J. 1998. Low genetic variation among killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the eastern North Pacific, and genetic differentiation between foraging specialists. Journal of Heredity 89: 121-128.

Reiss, D., and L. Marino. 2001. Mirror self-recognition in the bottlenose dolphin: a case of cognitive convergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5937-5942.

Rendell, Luke and Whitehead, Hal. 2001. Culture in whales and dolphins. Behavioural and. Brain Science 24(2):309-382.

Blumer, H. 1969. Symbolic Interactionism - Perspective and method. University of California Press.

Ford, John. K. B. 1991. Vocal traditions among resident killer whales (Orcinus orca) in coastal waters of British Columbia. Canadian Journal of Zoology 69: 1454-1483.

Garrett, Howard. 2004, Do Orcas Use Symbols? http://www.orcanetwork.org/nathist/symbols.html

Herman, Louis. M., Pack, A. A. and Wood, A. M. 1994. Bottlenose dolphins can generalize rules and develop abstract concepts. Marine Mammal Science 10:70-80.

Hoelzel, A. R., Dahlheim, M. & Stern, S. J. 1998. Low genetic variation among killer whales (Orcinus orca) in the eastern North Pacific, and genetic differentiation between foraging specialists. Journal of Heredity 89: 121-128.

Reiss, D., and L. Marino. 2001. Mirror self-recognition in the bottlenose dolphin: a case of cognitive convergence. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98:5937-5942.

Rendell, Luke and Whitehead, Hal. 2001. Culture in whales and dolphins. Behavioural and. Brain Science 24(2):309-382.